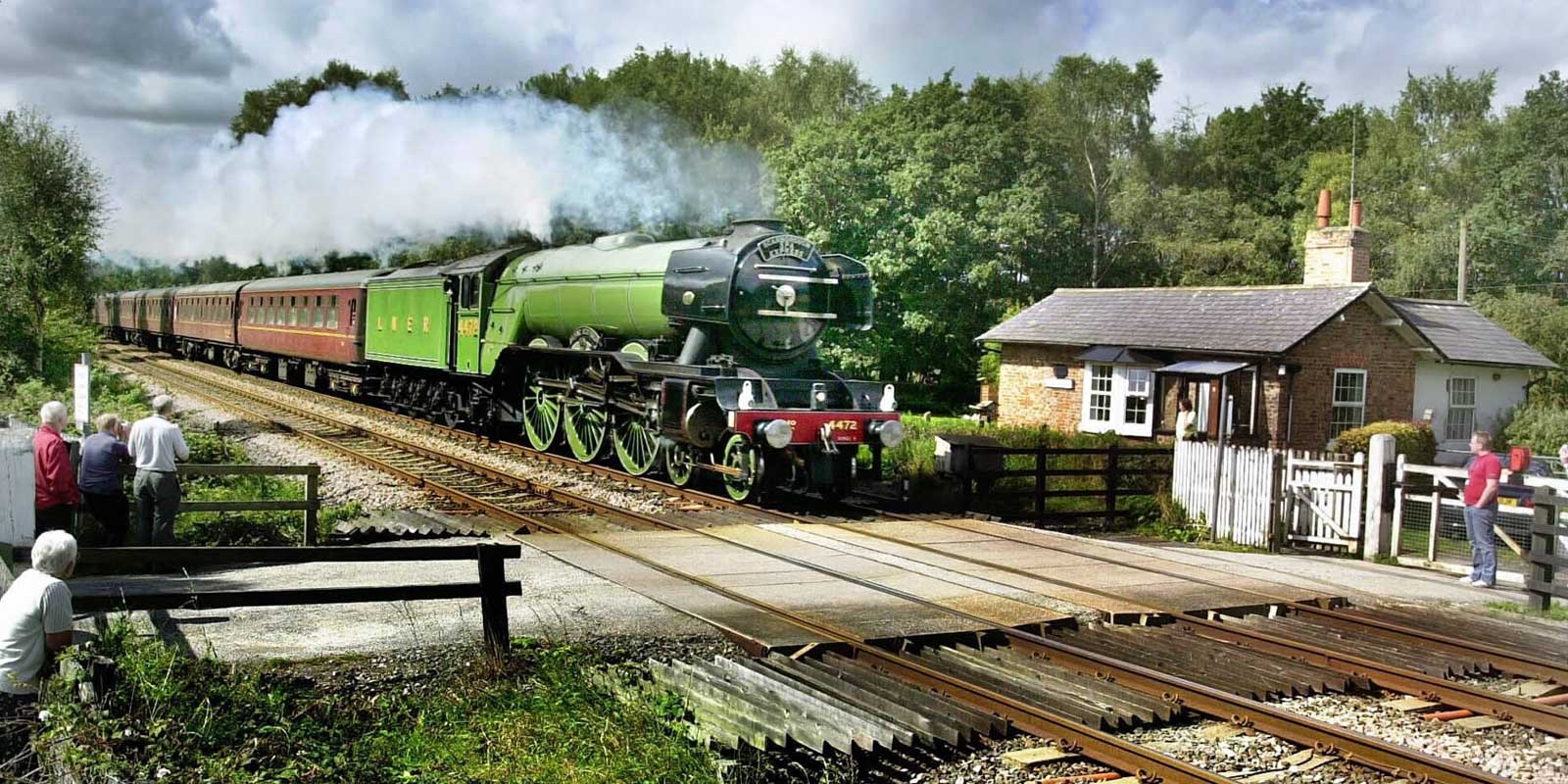

Travelling by steam train evokes a hopeless sense of nostalgia for

Britain's great, pioneering railway past, combined with the simple

delight of seeing an enormous plume of steam bursting from a train as

it pulls out of a station. Steam was all but extinct by 1968, and

engines were sent to scrap yards, but thanks to heritage railway

companies, who have rescued and restored many locomotives and lines, it

is back from the brink.

Around 100 different lines, some little more than a mile long, have

been reopened. Stations have been restored to their period appearance,

with old bicycles propped against picket fences, retro billboards

advertising Woodbine cigarettes and Lyons tea, plus little benches and

immaculate flower beds. Station masters and ticket collectors wear

proper, period uniforms. It is all part of the fantasy and romance of

travelling by steam train. Whether it is to satisfy your own interest

or your children's obsession with Thomas the Tank Engine, travelling by

steam offers a wonderful day out for locals and visitors alike.

British Rail Travel:

Where Have All The Railways Gone?

LNWR postcard, 1904

After growing rapidly in the 19th century during a period best

described as Railway Mania, the British railway system reached its

height in the years immediately before the First World War, with a

network of 23,440 miles (37,720 km). After the First World War the

railways faced increasing competition from a growing road transport

network, which led to the closure of some 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of

passenger railway between 1923 and 1939. Some of these lines had never

been profitable and were not subject to loss of traffic in that period.

The railways were busy during World War II, but at the end of the war

they were in a poor state of repair, and were soon nationalised as

British Railways.

The Branch Lines Committee of the British Transport Commission was

formed in 1949 with a brief to close the least-used branch lines; 3,318

miles (5,340 km) of railway were closed between 1948 and 1962. By 1961

losses were running at £300,000 a day; since nationalisation in

1948, a further 3,000 miles (4,800 km) of line had been closed, railway

staff numbers had fallen 26% from 648,000 to 474,000 and the

number of railway wagons had fallen 29% from 1,200,000 to

848,000. This period saw the beginning of a closures protest movement

led by the Railway Development Association, whose most famous member

was the poet John Betjeman. They went on to be a significant force

resisting what became known as the Beeching proposals.

British Rail Class 122 diesel mechanical multiple unit, built in 1958.

In the early 1960s, two reports - The Reshaping of British Railways

(1963) and The Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes (1965),

written by Dr Richard Beeching and published by the British Railways

Board - were presented to Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, and his

government, which recommended more reductions of the network and

restructuring of the railways in Great Britain. The first report

identified a further 2,363 stations and 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of

mostly rural and industrial lines for closure, 55% of

stations and 30% of route miles, with an objective of

stemming the large losses being incurred during a period of increasing

competition from road transport and reducing the rail subsidies

necessary to keep the network running; the second report identified a

small number of major routes for significant investment. The 1963

report also recommended some less well publicised changes, including a

switch to containerisation for rail freight, and that freight services

should mainly be for minerals and coal.

Eager to save more money, the Government implemented the

recommendations of the reports, with what became known as the Beeching

cuts. Protests resulted in the saving of some stations and lines, but

the majority were closed as planned and Beeching's name remains

associated with the mass closure of railways and the loss of many local

services in the period that followed. A few of these routes have since

reopened, some short sections have been preserved as Heritage Railways,

while others have been incorporated into the National Cycle Network or

used for road schemes; others now are lost to construction, simply

reverted to farm land, or remain derelict.

Line closures, which had been running at about 150 - 300 miles per

year between 1950 and 1961, peaked at 1,000 miles (1,600 km) in 1964

and had come to a virtual halt by the early 1970s. Not all the

recommended closures were implemented. Lines through the Scottish

Highlands, such as the Far North Line, were kept open, in part because

of pressure from the powerful Highland lobby. Other routes (or parts of

routes) planned for closure that survived include the Settle-Carlisle

Line, Middlesbrough-Whitby, Ipswich-Lowestoft and Manchester-Sheffield

via Edale. Other closures had been met with such vociferous public

opposition they were quietly shelved.

Dent Station, Settle-Carlisle Line

The public wanted Beeching's head; he resigned as chairman of the

British Railways Board, effectively marking the end of the cut and

slash train policy. The strength of feeling against the shrinking of

the rail system has remained to this day - from those who lived through

the changes to later generations who know of it only through the poetry

of John Betjeman and the romanticised vision of Britain in the Fifties

seen in films such as 'The Railway Children'. It is impossible to think

of a politician let alone a civil servant whose name is still held in

such ignominy half a century later. The impression of Beeching as the

heartless vandal resonated so much that 30 years after he left office,

the BBC could still call a sitcom based on a rural branch line Oh Dr

Beeching. Beeching's name even lives on infamously in the names of

streets and houses located near disused stations.

Reshaping the railways meant life in the country would never be the

same again - and the effect in terms of decades of underinvestment in

railways has become evident. However, in recent years, as roads have

become more congested and car travel more expensive, the number of

people on the trains has increased significantly. Hundreds of miles of

track have been slowly reopened and stations refurbished. Today there

are also more than 100 heritage lines that have been restored by

enthusiasts and local volunteers to give a glimpse of the age of the

steam train.

Design by W3layouts