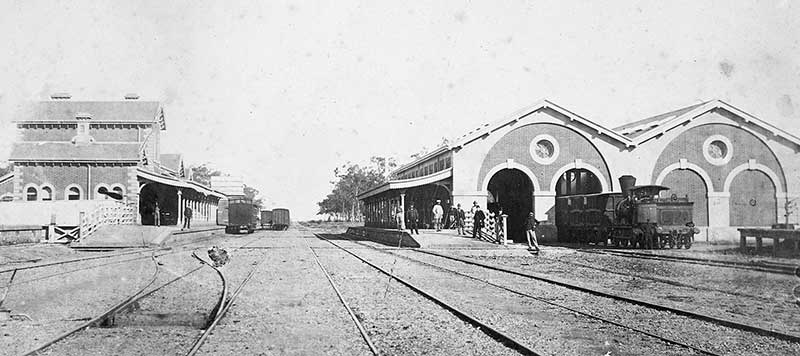

Serviceton yard, SA

A rail yard, railway yard or railroad yard as they are known in America, is a complex series of railway tracks for storing, sorting, or loading and unloading railway wagons, passenger carriages and sometimes locomotives. Railway yards have many tracks in parallel for keeping rolling stock stored off the mainline, so that they do not obstruct the flow of traffic. Rolling stock is moved around by specially designed yard shunters, a small but powerful type of locomotive. Rolling stock in a railway yard may be sorted by numerous categories, including by type, loaded or unloaded, destination, wagon type, or whether they need repairs.

Just about every railway station around Australia had a yard of sorts; though more often, it was a siding, connected at one or both ends to the main line. Rarely used these days, sidings were generally attached to smaller stations, consisting of one or two lines parallel to the main line opposite the station, with a goods platform, storage shed and sometimes a platform crane to load and unload heavy or bulky goods. Wagons could be left by passing freight trains at the goods platform, then picked up later on the return journey. In grain growing areas, huge concrete grain silos were constructed alongside these sidings when the silos came into widespread use in the 1920s.

At locations where there was only a single track which carried traffic in both directions, sidings often took the form of a loop line alongside the main line. Sidings like these are still in use on isolated stretches of track such as the east-west line across the Nullarbor Plain where a slow moving train can pull off the main line into a siding to allow a faster moving train to pass, or a train travelling in the opposite direction to also pass. Loop line sidings often had water towers installed where steam locomotives could be topped up with water without hindering the flow of other traffic on the line.

During the very early days of steam locomotives, water stops were necessary every 10 to 20 kms and consumed much travel time. With the introduction of tenders (a special car containing water and fuel), trains could run 150–250 km without a refill. Water stops employed water tanks, water towers or tank ponds. The water was at times pumped by windmills, and sometimes by hand pumps, often by the train crew themselves.

Beresford Siding, SA

Driving along the old Ghan train track are a couple of hulking structures alongside the road at places like Curdimurka and Beresford Sidings which have been restored by the Ghan Preservation Society. These elevated cast iron water tanks were used to water early steam locomotives. Associated with the water tanks are water softeners made by the Kennicott Water Softener Co Ltd in Wolverhamp-ton, Staffordshire between 1922 and 1962. These water softeners used a process discovered by Kennicott in 1902 to remove dissolved limestone from hard water by exchanging bicarbonate with sodium ions.

The water softener at Beresford, for example, was installed during World War II to treat mineralized bore water and to prevent lime and gypsum building up in steam train engines. As is the way with progress, such water softeners became redundant when the trains began to be powered by diesel engines in 1954. Once the water and de-mineralisation towers lost their usefulness, they were simply abandoned along with their loop sidings.

Larger railway yards are generally located at strategic points on a main line. Main-line yards are often composed of an up yard and a down yard, linked to the associated railroad direction. There are different types of yards, and different parts within a yard, depending on how they are built.

As well as loading and unloading of goods, larger yards have space for storage of wagons and passenger carriages while they are not being loaded or unloaded, or are waiting to be assembled into trains. The assembly and dis-assebbly of trains employs a process known as shunting. Large yards may have a tower to control operations.

A hump yard has a constructed hill, over which freight cars are shoved by yard locomotives, and then gravity is used to propel the cars to various sorting tracks

A gravity yard is built on a natural slope and relies less on locomotives; generally locomotives will control a consist being sorted from uphill of the cars about to be sorted. They are decoupled and let to accelerate into the classification equipment lower down.

A flat yard has no hump, and relies on locomotives for all car movements.

Echuca Engine Shed

In the days of steam when traffic was much greater than it is today, it was not uncommon for locomotives to be stored at station sidings along the line in engine sheds. The most common sheds were substantial buildngs, often made of brick, with one or two tracks or roads in the loco sheds of smaller towns, and three or more tracks at busier locations. Many sidings, especially those where services terminated, also had a turntable, many of which were operated by hand. After changing their direction on the turntable, the locomotive would use a loop line to rejoin the train at the other end and be again facing the direction of travel.

Aditional to an engine shed was a coaling station, water tank, water tower or tank ponds. The latter were created by damming small creeks that intersected the tracks in order to provide water for water stops. When a train stopped for water and was positioned by the water tower, the boilerman swung out the spigot arm over the water tender enabling the locomotive to take on water.

In remote areas where steam locomotives stopped only to take on water and sometimes coal, small communities were created to house the workforce that serviced the trains passing through. Once diesel locomotives replaced steam engines, the coaling and water stops became obsolete. In deserted areas like the Nullarbor Plain, once the people moved away, all that was left was a ghost town.

Tarcoola, SA, now a ghost town

Design by W3layouts